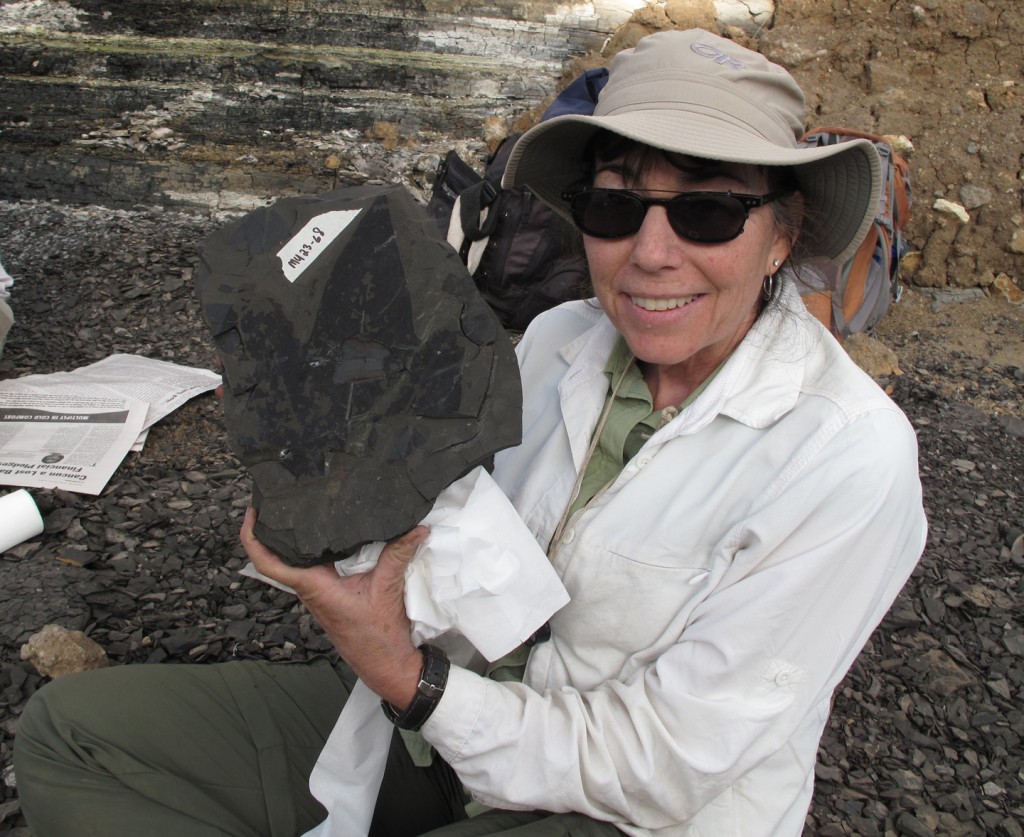

Close your eyes and imagine a paleontologist driving a pickup truck out into the badlands of Wyoming to study the most celebrated dinosaur-bearing rock formation in the US and accompanied only by two dogs. Now answer me truthfully, did the paleontologist look like this?

Paleontologist & Geologist at Uinta Paleontological Associates, Inc.

PhD and MS from University of Wyoming, BA from Western State College

Field sites past & present: Wyoming, Colorado

When I wrote to Dr. Kelli Trujillo asking her for a picture of herself doing fieldwork, she replied, “I only have field photos of me teaching, since I’m almost always in the field alone.” Luckily, her work as a paleontological consultant has led to fossil discoveries that require her to supervise fossil excavation crews, and so she could share the picture above. Pity her pups can’t take pictures of her doing fieldwork, though – maybe they’d do better at getting her smiling (beardless) face in a shot!

Kelli is a vertebrate paleontologist who works on the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation (~155-148 Ma). Beginning in the 1870’s, the Morrison has been THE place to find dinosaurs in the American West, so much so that it was at the center of the legendary “Bone Wars” between rival paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh (Peabody Museum) and Edwin Drinker Cope (Academy of Natural Sciences). Thanks to intense collection over 140+ years, many species of dinosaurs have been described from the Morrison, including fan favorites Stegosaurus (Colorado’s state fossil), Allosaurus (Utah’s state fossil), and lots of sauropods. While its dinosaurs are extremely well-studied, the Morrison Formation itself needs more work.

Kelli’s research includes detailed mapping of Morrison outcrops, analyzing the composition of the sediments in order to better understand the environment in which the many dinosaurs lived and died, and obtaining more radiometric dates from different Morrison outcrops to help figure out just how many of these dinosaur species lived at the same time. She also digs quarries and carefully screenwashes the sediments to collect microvertebrate remains –these small animals of the Morrison, not the dinosaurs, are most useful in reconstructing the paleoenvirnment.

A significant portion of Kelli’s career has been in paleontological education, both in formal and informal settings. As a consultant, she works with developers and construction agencies to ensure that our nation’s paleontological resources are properly collected and preserved. As manager of the University of Wyoming Geological Museum, she has introduced thousands of elementary through high school students to the wonders of dinosaurs and paleontology. She also teaches undergraduates and volunteers to clean sediments off of fossils in the museum’s preparation lab, which is visible to the general public. Each summer, Kelli leads fieldtrips in the Morrison Formation for college students from the University of Wyoming and the University of Pittsburgh. She teaches them how to be field paleontologists and gets them digging in the dirt, discovering new fossils. And, of course, most of them love it!