Curator, Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture

PhD from UC Berkeley, MS and BA from Lund University

Field sites past & present: Colombia, Argentina, Greece, Spain, Turkey, Sweden, China, not to mention 16 states

My goals for this blog are not just to broaden people’s perception of what a paleontologist looks like, but also to show the diversity of research that paleontologists do. Only a fraction of us study dinosaurs; our study organisms may not be as sexy, but the research questions we can answer are! So far, we’ve seen scientists who study fossil leaves, molluscs, human ancestors, and molecules. Now let me introduce you to another kind of microscopic fossil that is crucial to understand when and why grasslands came to cover so much of Earth’s surface and to one of the top American scientist working on these tiny fossils.

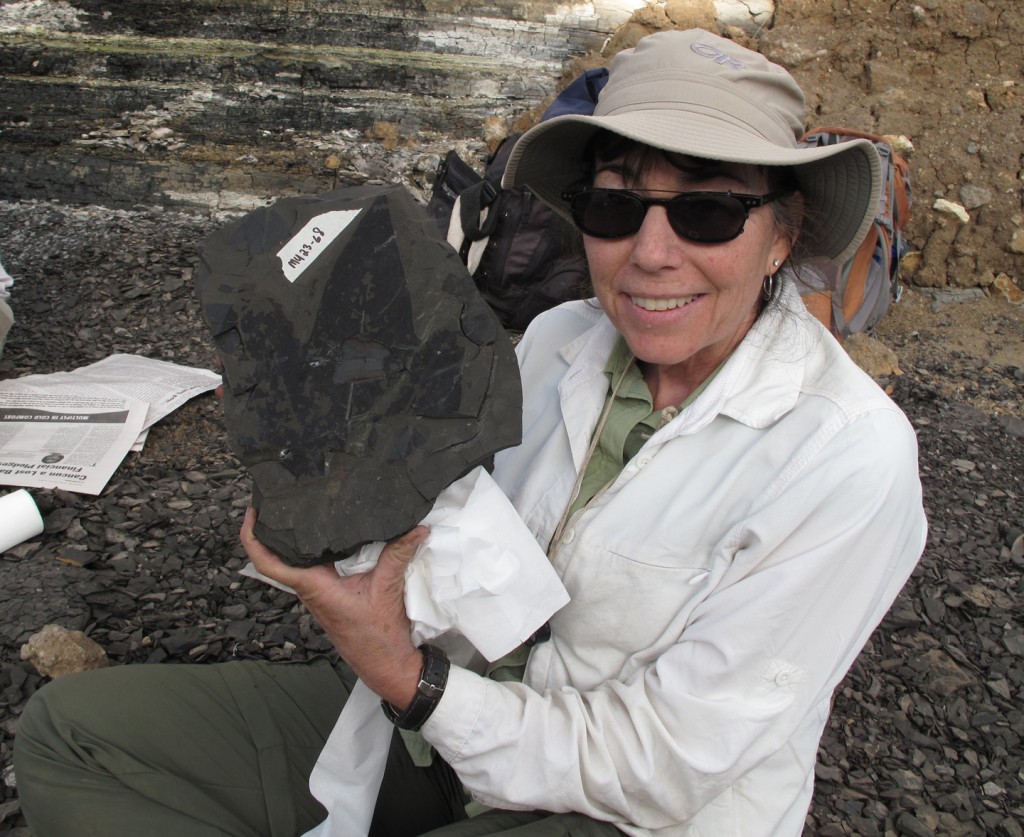

Dr. Caroline Strömberg is a pioneer in the study of phytoliths (translated from Greek as “plant stones”), the microscopic pieces of silica that form in some plant cells. Phytoliths record the shape of the plant cells in which they form, and different plant groups have differently shaped cells and thus distinctive phytoliths. Grasses in particular are rich in silica (hence, animals like horses that eat predominantly grasses have really long teeth), and so while grass body fossils are rarely preserved, their phytolith remains are. Thus, by studying phytolith assemblages preserved in fossil soils, it is possible to reconstruct past vegetation and look at the transition from the forest ecosystems of the early Paleogene to the open, grassland ecosystems that are abundant today.

Caroline has done fieldwork in places around the world that are grasslands today, trying to figure out when the transition happened, whether it was synchronous worldwide, and what might have triggered this profound ecological shift. She is also interested in the coevolution of grasses and grazing animals. In her final year of graduate school, Caroline won Best Student Paper awards at the annual meetings of both the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology and the Paleobotanical Section of the Botanical Society of America. (It’s my last week of classes and I don’t have time to fact check, but I’d bet Caroline is the only person to win both of those awards!) On a totally non-related note, I have to mention that Caroline is second author on a Science paper detailing the implications of finding grass phytoliths in dinosaur poop.

Looking for advice on what to do for a postdoc? Let me present the Caroline Strömberg example. By the end of graduate school, Caroline was already widely recognized for her phytolith work. She could easily have kept only that focus and had a very successful career. But, she viewed the postdoc years as a chance to pick up new skill sets and make herself a more complete scientist, so she came to the Smithsonian to work on Cretaceous leaf fossils with Dr. Scott Wing. What a piece of luck for me!

People are often classified as left-brained or right-brained, but what do you call a person who is creative and artistic as well as scientific and logical? I’ve been the beneficiary of fantastic hand-drawn cards, witnessed Caroline put together some really brilliant costumes (no detail is too small), and been part of some hilarious practical jokes. One of my favorites, from the only time that Caroline and I were in the field together: for many years, Scott has been expounding on the why the giant sunglasses they give people after cataract surgery make the best field sunglasses. Well, Caroline and I decided that they were not nearly fashionable enough, and somehow managed to “borrow” Scott’s sunglasses AND find glitter in Worland, Wyoming! Field fashion at its finest.